Understanding Structural Racism in Making History.

You can intervene.

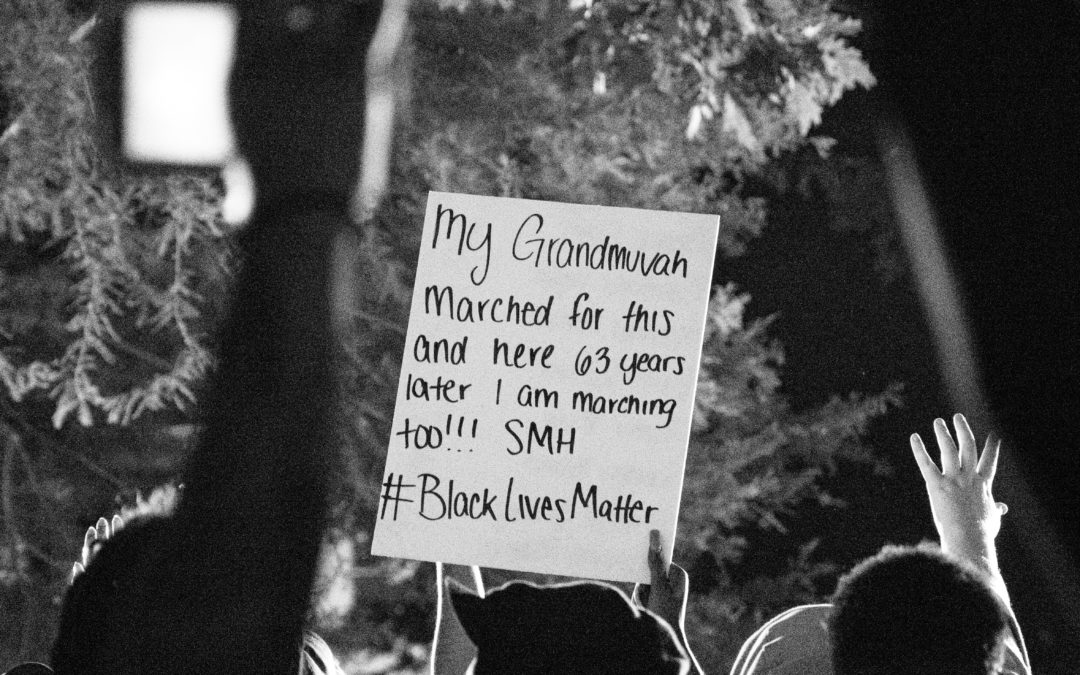

American history forgets — it has a solid way of weeding out victories and progress achieved by non-dominant groups. A chain of historical events built structures that disallow diversity in history — that’s structural racism. This quick skip through history-making shows how these structures ensured whitewashed, msculinist history and the slow inroads into that structure that we’re still forging.

Shortly after the Civil War, the US developed graduate study modeled on the great European universities. As a result, a rising tide of African American, female, indigenous, LGBTQ, and other voices were stifled as what counted — as history professionalized itself.

After World War I, government officials started nurturing federal archives, where the records of what happened at top levels of government would be collected — the goal was to save all the work of “great men of public letters.” That was the focus of America’s saving and our subsequent learning. The next few decades saw a slow and selective increase of regular document-saving, but mostly at the highest level of government.

As the 1950s unfolded, a few minority and women’s voices started to be heard and saved… hemmed in by being portrayed as “special” people who stood above the rest in their respective groups. Anomalies.

In the 1960s, those graduate school programs became an income source. Universities expanded quickly, and in its need for students opened the gates to a rush of people of color, women, LGBTQ, and the working class. This is hugely significant because those graduate students went to the archives to find the historical data to research what they wanted to know about: their own people, challenges to big events, and a whole parallel history. Archives were not ready.

In the 1970s, those minority graduate students from the 60s attained tenured, curriculum-writing positions. They insisted that there is more than one lens through which to view history. Students looked for the proof, asking librarians and archivists to change their collection criteria. Often if folks wanted evidence, they had to go make it through recording oral histories, writing correspondence, or conducting surveys.

In the 1980s and 1990s, non-dominant stories and data were sought out — often from a standpoint of complementing “the master narrative.” After that, the internet hit the scene and available voices multiplied… exponentially! Dismantling Racism TCA

But what is saved is still inadequate to the task. The dominant narrative of high achievement and traditional ideas of success still drives many of the women and people of color that I have spoken with to say, “yes! great! But no, not me. Not my story.” Some national directives are hopefully making inroads into that traditional idea of history…

I have consulted with archivists at the African American Museum of History & Culture and the YIVO Institute for Jewish Research about what my clients are saving. I’m also consulting field trips and curricula as they develop at the National Women’s History Museum — watching the cyber museum plant a stake in the ground and grow.

A first step to correcting structural racism and sexism in the archives is to consider adding your own archive to a local or national repository.

Yes. Your story.

Not sure where to start? I have a free guide listing the possibilities, and also some recommendations about what not to save. Sign up here.

I spent 18 years as “archivist and senior research scholar” at an academic science library, actively trying to add women to the historical record and looking for the women who were already included almost accidentally. I have degrees in women’s history and cultural theory — the latter means that I see the cultural value of everyday practices such as food, clothing, hobbies, and domestic arrangements. Non-famous people matter.

I spent 18 years as “archivist and senior research scholar” at an academic science library, actively trying to add women to the historical record and looking for the women who were already included almost accidentally. I have degrees in women’s history and cultural theory — the latter means that I see the cultural value of everyday practices such as food, clothing, hobbies, and domestic arrangements. Non-famous people matter.